“Write what you know.” That’s common advice most writers will recognize. But Eugene Peterson ’54 has become a pastor and a writer who inspires Christians — including artists — by doing just the opposite. He learned to write about what he didn’t know.

In his new memoir, The Pastor, Peterson recounts a period of soul-searching during which he discovered what he calls “heuristic writing.”

“It was a way of writing that involved a good deal of listening, looking around, getting acquainted with the neighborhood,” he writes. “Not writing what I knew but writing into what I didn’t know, edging into a mystery. … Writing as a way of entering into language and letting language enter me, words connecting with words and creating what had previously been inarticulate or unnoticed or hidden. Writing as a way of paying attention. Writing as an act of prayer.

This work of paying attention to what he describes as “the invisible that energizes and shapes visibility” has been cultivated by his attention to the arts.

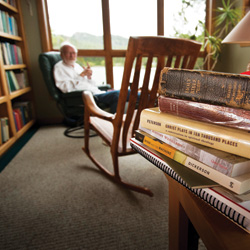

Peterson is author of more than 30 books, including The Message, his paraphrasing translation of Scripture. He received the Denise Levertov Award in 2009 from Image, the quarterly arts journal housed on Seattle Pacific University’s campus — an honor for people who do exemplary work at the intersection of faith and art.

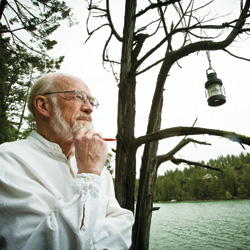

In The Pastor, Peterson draws from 29 years as pastor of Christ Our King Presbyterian Church in Bel Air, Maryland. He wrote the book from his Lakeside, Montana, home, where he lives with his wife, Janice. He spoke to Response about how a richer understanding of art can lead to a richer experience of faith.

What are your earliest memories of encounters with art and with artists? Did any stories, songs, or performances make strong impressions on you?

No, virtually none. I grew up in a very sectarian world. We were the only Christians in our Montana town, and so I had no exposure to art as such. I grew up in a storytelling family, but it was an oral world. We didn’t have many books. The town itself was totally devoid of anything that had to do with art.

I was always in the school band when I was in high school. I played a cornet, and I played it loud. That’s the way I made up for my lack of skill. I would’ve loved to have played in a dance band, a jazz band. But in our Pentecostal church, that was “off-limits,” so I sacrificed that for the Lord.

So I didn’t have much exposure to art until I went to college at Seattle Pacific. There, it was mostly through literature. I studied philosophy and English, and I was the editor of the Tawahsi yearbook my junior year. That was my first experience getting a feel for art, working with the publisher and with a photographer who took a lot of pride in his photography — he was an artist.

Poetry was the first art form that gave me the sense that I was in on something I didn’t know anything about.

My final year at SPC, I was president of the student body, and I wrote a column for the student newspaper, The Falcon. I had an English professor at Seattle Pacific who took an interest in me, Elva McAllaster. She was the advisor to the paper. I had never taken a course in writing at all, but she became kind of a writing teacher for me. I remember — I wrote a sentence that said, “This was duller than calculus and Chaucer.”

And she said, “Eugene, have you ever read Chaucer?”

I said, “No, but I just kind of like the sound – ‘calculus and Chaucer.'” So she sent me some Chaucer, and I thought, “Oh, wow, this is not dull!”

She kept in touch with me for another 20 years. Every time I’d write something, she would comment on it.

In The Pastor, you talk about some of the artists you’ve gotten to know, and the influence they’ve had on your faith. How did you first begin to develop relationships with artists?

I stumbled along on the fringes of the art world until I went to seminary in New York City. Then I plunged into the whole world of art and relished it.

One of the assignments I had as a seminarian was to do field work in a church. My primary responsibility was “the 20–30 club,” a young adult group. They were all artists, all single, and all from someplace else. They were in New York to dance, to make it on Broadway, or to be poets. None of them made their living by art. They were waiters and waitresses and taxicab drivers and shoe salesmen, anything they had to do to make a living.

I listened to them talk about their art and how hard it was to get auditions and showings. Then I started going to museums. And Jan and I went to the theatre. It was easy in those days to get really cheap seats to off-Broadway plays. In fact, theatre is probably one of my most preferred art forms. It just seems very congruent with the gospel — embodying things instead of just saying them. When it’s done skillfully, you enter the world of the play. It strikes me as being very incarnational. The Word becomes flesh and walks through the neighborhood.

During that time, I think I got a feel for the kind of life that artists live, the kind of precariousness of their life, how much disappointment goes into pursuing a way of life which is lucrative for very few people. I gained a certain kind of respect and admiration for that way of living. This has stood me in good stead during a lot of the years in which I was a pastor.

How have the arts shaped your vocation as a pastor?

Artists have contributed a lot more to me than I have to them. I spend a lot of time talking with artists. And I think they need appreciation.

Several times at Christ Our King Church, we put on plays. The first one I remember was The Boy With a Cart, the Christopher Fry play. It was just absolutely stunning. People from my congregation made up the cast. Our church was in-the-round so we had seating in four sections. It was a perfect place for theatre. I didn’t have many in my congregation who were artists, so I was one of the few people to give witness to the fact that what they were doing was really important for the gospel, for the kingdom.

I think the people who have influenced me most as a pastor haven’t been the theologians — they’ve been the artists.

From artists I learned never to look at just the surface of a person, but to look for the interior life, to consider what I know of their past. An exterior is never just an exterior. In our culture, we’re trained to focus on the exterior, for instance, through advertising and publicity. Being present to a person long enough to start sensing that they’re never just themselves, they’re their parents, their grandparents, their kids, their neighbors — all of that becomes part of their story. Artists help me do that, because they are attuned to the interior life.

I think it’s interesting that Karl Barth, the theologian who has influenced me most, was mostly influenced by Mozart. Mozart was a theme in his life. I think he learned a lot about writing theology by listening to Mozart.

You’ve written extensively on the artistry in the Psalms and in Christ’s parables. How can we learn to appreciate the art of the Bible?

We grow up in America in the school system with very little exposure to art. Learning is mostly a matter of acquiring information. We’re trained to recognize truth as information. We don’t get much help in seeing things as a whole, in context, in relationship — I guess you could call it “an ecological imagination,” where everything fits, where everything goes together in some way.

That’s why the Scriptures are impenetrable to so many people, because we read them looking merely for information.

The Psalms, which are the center of the church’s prayer life, are probably the least-appreciated part of the Scriptures because they’re poetry. They’re treated so selectively. People have their favorite psalms, but we’ve lost the old habit of the church of reading through the Psalter, reading them all in sequence over a period of a month or two. You’re practicing a form of lectio divina when you’re praying the Psalms. You hear psalms read at funerals and weddings, but we’ve lost this immersion in the Psalms.

When we approach the biblical text, instead of asking, “What does it mean?” — which is what people usually do — we should ask, “What is it doing? How do I enter into this? How does it enter into me?”

You know, it’s surprising: We have Jesus as the centerpiece of what we’re doing, but he almost never talked in terms of explaining. He was always using enigmatic stories and difficult metaphors. He was always pulling people into some kind of participation.

It’s essential for us to develop an imagination that is participatory. Art is the primary way in which this happens. It’s the primary way in which we become what we see or hear.

I think a pastor is in a unique position to cultivate this participatory imagination. We shouldn’t just be giving information, because so much of what we’re dealing with is entangled with the invisible, the inaudible, the unsayable.

You and your wife, Jan, have said that hospitality is a subject that’s very close to your hearts. How can the church become more hospitable to artists?

One of the things that we did in our church was this — in cleaning up after a worship service, I’d find that a kid had been doodling all over the church bulletin. And some of these pieces were really interesting.

So I started inserting a blank piece of paper in all the bulletins and suggested to the kids in the congregation, “If you get tired of listening to me, just draw a picture and see what happens.” I’d collect these afterward. Every once in a while there would be one that was just stunning, and I’d use it as a bulletin cover. Through the years, we collected these bulletin covers and sometimes put them on display.

The kids – they were artists, and they were recognized for something that kind of escaped the norm of what happens in church. None of them went on to become Picassos or Rembrandts. But who knows what might have happened?

I think the congregation is a really good place to develop an artistic mindset, but it’s got to be done cautiously without trying to make a program out of it or make a statement out of it. I’m more interested in finding the artists, encouraging them, listening to them, and exploring the world through their eyes and ears.

Read a review of The Pastor: A Memoir by H. Mark Abbott, former pastor of First Free Methodist Church and instructor in preaching in SPU’s School of Theology.

Read an excerpt from The Pastor: A Memoir