Scripture: Isaiah 40:3–5 (NRSV)

A voice cries out:

“In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord,

make straight in the desert a highway for our God.

Every valley shall be lifted up,

and every mountain and hill be made low;

the uneven ground shall become level,

and the rough places a plain.

Then the glory of the Lord shall be revealed,

and all people shall see it together,

for the mouth of the Lord has spoken.”

Question: What keeps you from truly preparing for Christ this Christmas?

“Fantasia On Greensleeves”*

Giving Birth to God’s Kingdom

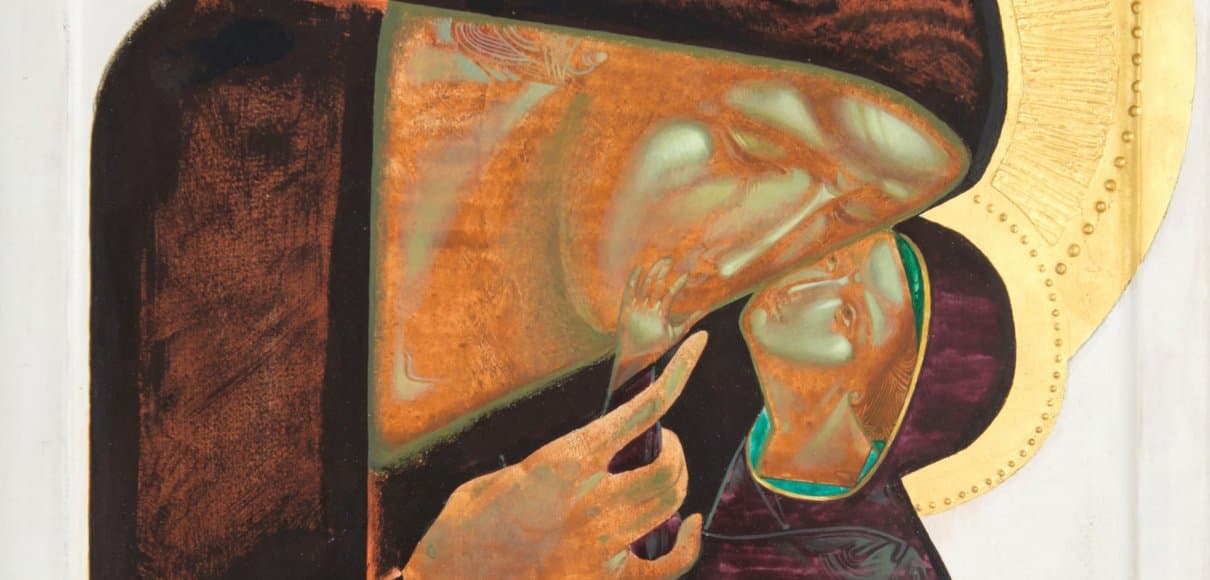

BIRTH, ANY BIRTH, is our primary access to the creative work of God. And we birth much more than human babies. Our lives give birth to God’s kingdom every day — or, at least, they should.

But the actual birth of Jesus has never been an easy truth for people to swallow. There are always plenty of people around who will have none of this particularity: human ordinariness, body fluid, raw emotions of anger and disgust, fatigue, and loneliness. Birth is painful. Babies are inconvenient and messy.

As it turned out, the ink was barely dry on the stories telling of the birth of Jesus before people were busy putting out alternate stories that were more “spiritual” than those provided in our Gospels.

Mountains are nice as long as they inspire lofty thoughts, but if one stands in the way of our convenience, a bulldozer can be called in to get rid of it.

In these accounts of the Christian life, the hard-edged particularities of Jesus’ life are blurred into the sublime divine. “Jesus was not truly flesh and blood but entered a human body temporarily in order to give us the inside story on God and initiate us into the secrets of the spiritual life.” And, “Of course he didn’t die on the cross, but made his exit at the last minute. The body that was taken from the cross for burial, was not Jesus at all but a kind of costume he used for a few years and then discarded.”

If we accept that version of Jesus, we are then free to live the version: We put up with materiality and locale and family for as much and as long as necessary, but only for as much and as long as necessary.

Those of us who take this point of view no longer have to take seriously either things or people. Anything we can touch, smell, or see is not of God in any direct or immediate way. We save ourselves an enormous amount of inconvenience and aggravation by putting materiality and everydayness at the edge of our lives, at least our spiritual lives. Mountains are nice as long as they inspire lofty thoughts, but if one stands in the way of our convenience, a bulldozer can be called in to get rid of it. Other people are glorious as long as they are good-looking and well-mannered, bolster our self-esteem, and help us fulfill our human potential, but if they somehow bother us, they certainly deserve to be dismissed.

But it’s hard to maintain this view of things through the Christmas season. There is too much stuff, too many things. And all of it festively connects up with Jesus and God. Every year Christmas comes around again and forces us to deal with God in the context of demanding and inconvenient children; gatherings of family members, many of whom we spend the rest of the year avoiding; all the crasser forms of greed and commercialized materiality; garish lights and decorations. Or maybe it’s the other way around: Christmas forces us to deal with all the mess of our humanity in the context of God who has already entered that mess in the glorious birth of Jesus.

Eugene Peterson ’54 was a pastor, professor, biblical scholar, and author of more than 30 books including his paraphrase of the Bible, The Message: The Bible in Contemporary Language. This abridged essay is reprinted with permission from Paraclete Press’ book God With Us.

*“Fantasia On Greensleeves”

Music: Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

©Oxford University Press

SPU String Orchestra