Amanda Stubbert: Welcome to the SPU Voices podcast, where we tell personal stories with universal impact. I’m your host, Amanda Stubbert, and today we sat down with Professor Cara Wall Scheffler. She is the professor and co-chair of Biology at SPU. Her research focuses on the evolution of human sexual dimorphism, how men and women differ physically, particularly in the context of balancing the pressures of thermoregulation and long-distance locomotion. She has been working on this problem for over 20 years now and has published numerous papers along with her students. Her work shows very clearly that different selection pressures have acted on men and women and that women in particular have a rare-among-mammals ability to work both efficiently and economically when carrying loads. Cara, thank you so much for joining us today.

Cara Wall Scheffler: Thanks for having me.

Amanda: Well, let’s start with, so a lot of what I just said, I think people would say, “Okay, what?”

Cara: (laughs)

Amanda: (laughs) “First of all, what do you mean? And second of all, why is that important?” So let’s start with just sort of the layman’s definition.

Cara: Yeah.

Amanda: You know, you’re sitting next to someone on an airplane and they say, “What do you do?” How do you describe it?

Cara: The quickest thing that I say is just I study how people walk, and I think that that sort of summarizes it. And I think the other piece is that I study how people walk at the intersection between biology and culture. And so I’m interested in how people manage what it means to, as you said so nicely, be a mammal, be a primate. We have to use a certain amount of energy. We have to maintain our thermoregulation, so we have to maintain a comfortable body temperature or else our body suffers. But humans also have a lot of social pressures: social pressures to be a good friend, potentially be a good parent, be committed to their social interactions, and so sometimes people have a tension between how they feel they’re supposed to act appropriately in a cultural context but also not get too hot, not use too much energy, and so I’m really interested in what decisions people make when their physiology and their anthropology intersect with each other.

“But humans also have a lot of social pressures: social pressures to be a good friend, potentially be a good parent, be committed to their social interactions, and so sometimes people have a tension between how they feel they’re supposed to act appropriately in a cultural context but also not get too hot, not use too much energy, and so I’m really interested in what decisions people make when their physiology and their anthropology intersect with each other.”

Amanda: Interesting. Okay. So I think I can understand on probably the more obvious level, like you’re trying to be an athlete, right?

Cara: Sure, yeah.

Amanda: You’re trying to run, and you’re getting overheated and you’re pushing your muscles to the limit, but you want to win the race, right?

Cara: Yep.

Amanda: So that makes perfect sense to me. But I know you’re studying this in more of a day-to-day, much broader context. Can you give us an example or two of more of the everyday example of that?

Cara: There are a couple of everyday examples that I can think of. Well, on the first hand, I think it’s helpful to recognize that even though we have so much flexibility today in terms of how we gain access to food and water, especially here in Seattle, that isn’t true for everybody. And so there is a sense that how much energy you need in order to do your tasks and how you’re going to get food in order to accomplish those tasks, from the perspective of how you’re going to manage your body temperature; when you can have water; how much water you can have if water is freely available. We might not think very much of it, but actually, a lot of people in the world think a huge amount about these, and food insecurity and water insecurity are things that are important for everybody. So I think that thinking about biology from those perspectives is not too foreign for a lot of people.

But that being said, I think that the easiest everyday example I have is that when people pick up their child, which is something they might do, particularly in Seattle when they’re late for a meeting, their kid is late to school. They’re going to pick up their kid and they’re going to start walking. The reason they pick up their child and how fast they go and their ability to be alert to their environment, that’s different. They treat that differently than if they’re walking back to their car with a bag of groceries. And I’m interested in how people make those kinds of speed and alertness choices depending on whether or not they’re with their child versus whether or not they’re with their groceries versus whether or not they’re on their phone versus whether or not they’re with their dog. So we have expectations as scientists that humans are going to behave a certain way because they’re mammals, but what ends up happening in different cultural contexts, different daily contexts, people actually make different decisions all the time, and I’m really curious as to when and how those decisions appear.

Amanda: Okay. So the temperature regulation, especially when traveling long distances, I can understand if you are in a country that is very hot and you have to walk miles to get decent water. That makes sense to me. But in this more everyday context of carrying the groceries and the child and getting to work and whatnot, how does that temperature regulation play into our Western society life?

Cara: Well, I mean, it ends up that temperature is probably the most acute cue your body receives as to how hard you’re working.

Amanda: Sure, yeah.

Cara: And even here, I have students go up and down stairs carrying loads during the winter here in Seattle, and even sort of reasonably fit 20-year-olds, when they start walking up and down stairs, they make different decisions about how they’re going to adjust what they’re carrying, how quickly they’re going to go, whether or not they feel like skipping steps at the bottom, and whether or not they want to stop. And I think that’s this other piece, that temperature is our body’s best way of telling you that you’ve done too much. And so even in winter in Seattle, we still see temperature sort of shutting people down, even when they have plenty of access to food, they’re happy to stop and drink. They’re still listening to the cues that their body’s temperature is giving them.

And then there are athletes everywhere, and we do know from other kinds of studies that that’s the first thing that’s going to stop somebody running a marathon. Or here in Seattle we have a lot of ultra and the kind of athletes that are excited to run up and down mountains and then swim across lakes and things like that, and the likelihood of them stopping is dictated by the range of temperature their body’s going to allow them to go.

Amanda: Is this like a nature and nurture, like most things in life? Those ultra marathon type folks — that will never be me, not even for a second.

Cara: (laughs)

Amanda: I’ve always said I would rather walk 10 miles than run 1. So that’s just me. But is that because I was born that my temperature regulation is not just naturally so even that I can train for something like that?

Cara: Yeah, I mean, there…

Amanda: Tell me it’s not my fault and I’m not just lazy.

Cara: Yeah.

Amanda: I’m just kidding. (laughs)

Cara: I mean there is always going to be a motivational component. I mean, people can train their body to do all sorts of things, and maybe because I live in America and I can sort of see the wide range of nurturing options, I will always put forth a nurture over nature idea. We all have a genetic potential, but we can push our bodies physiologically, should we train, should we choose, should we choose to train for that kind of lifestyle. And then there are these other components where because I study women so closely and women have all sorts of different physiologies depending on where they are in their lifespan. I study pregnant women, so maybe they’re pregnant. I study lactating women. Maybe they’re lactating. I study women at different phases of birth control, women who are cycling through different phases of ovulation. And so women get to do a lot of super cool things, all of which impact their thermoregulation, all of them. And so that’s one of the reasons my interest in thermoregulation started, because women can continue to do some pretty remarkable things regardless of what is going on with their body temperature going up or down or whatever. There is a biology component for sure, but then you can also choose how you want to deal with that.

Amanda: Yeah. Well, let’s talk about women specifically. You’ve made some discoveries about women’s unique abilities. What has surprised you and even … I know there’s a few things that have even shaken up this generalized view of women.

Cara: Nothing has really surprised me in the sense that I did go into research with the idea that women were going to be better than everybody had always assumed, hypothesized, put forth. And I think one of those is that I do have an evolutionary perspective, and so I do study creatures on Earth, organisms from this perspective that organisms have to accomplish a set of things in order for their population to be sustained. So they have to gain access, as I said, to food and water and reproductive opportunities as a species, even if at the individual level, individuals might do things differently. And so for humans to be as successful as humans are, humans have to be able to successfully reproduce as a species, and that sort of nexus falls on women and women’s bodies. Some of the literature as I was coming out that suggested that women couldn’t be endurance athletes or couldn’t walk as effectively or were encumbered by their uterus …

Amanda: (laughs)

Cara: That’s just not reasonable.

Amanda: Yeah.

Cara: That isn’t reasonable. There are eight billion humans in every climatic zone on Earth. You can’t do that unless your females do a good job. You just … That isn’t reasonable.

Amanda: Right.

Cara: And so I went into it really trying to understand, why would people say that women weren’t good walkers? Why would people say that culture can’t be flexible enough to include women when necessary, to hunt or to gather or to process or to whatever or to walk 20 miles because that’s the only way you’re going to get to the next water source? It’s not reasonable from an evolutionary perspective, much less from an ethical or moral perspective, to say that women can’t do that or that women haven’t been asked to do that in order to make sure that their family and community survives. Of course we know that they have.

“I went into it really trying to understand, why would people say that women weren’t good walkers? Why would people say that culture can’t be flexible enough to include women when necessary, to hunt or to gather or to process or to whatever or to walk 20 miles because that’s the only way you’re going to get to the next water source? It’s not reasonable from an evolutionary perspective, much less from an ethical or moral perspective, to say that women can’t do that or that women haven’t been asked to do that in order to make sure that their family and community survives.”

Amanda: Yeah.

Cara: And so when I started investigating how women could manage their environment, the environment in which they find themselves over and over again, I was expecting women to be good at something, because humans are really good and you just can’t do that on a one sort of sex or gender situation. You mentioned in my introduction this idea that women are both good economically and efficiently, and this is a metabolic energetics argument about how mammals, so creatures that are generating their own heat, how they manage energy. And women, on average across humans, are always smaller than men in any sort of, wherever you’re measuring. On average, women are smaller, and this means that because metabolic energy — the amount of energy you do for everything — is directly correlated with how big you are, this means that women on average use less energy, just across the board. Because they’re smaller, they have less mass, they use less energy. Nobody’s going to argue with that. That’s just sort of physics.

Amanda: Yeah.

Cara: But the idea would be that when people who do biomechanics or exercise phys or comparative environmental physiology would come in and say, “Well, when you compare small mammals to big mammals, there’s an efficiency part for how much energy you use to do a particular task.” And so the idea would then be even though females are more economical, they use absolutely less energy, they’re not very efficient at what they do for a variety of reasons. They don’t have as much muscle mass or the ratio of pelvis to shoulder width is not great for locomotion, or whatever it might be, all these things. And so women might use less energy — until they start reproducing and then they use so much energy — but men are more effective, efficient, less prone to injury, all of these other pieces. These are all testable hypotheses. And so that is what I went out and did. I think it did surprise me how good, how large of a delta females are in comparison with men at certain tasks, because I think I expected it to essentially be equivocal, like yes, women are smaller so they’re using less energy, but basically their efficiency is relatively the same. Like we all use energy to do a particular task in some sort of comparable way.

But it actually ends up that women aren’t just comparable, there are some tasks that they actually do better. They’re way more economical, and also they are more efficient. So they do the exact same task for less energy per kilo of their mass, for a particular speed, for their own body size, whatever it might be. And that I wasn’t really expecting to find, and so those studies have probably been some of my favorites that I’ve done.

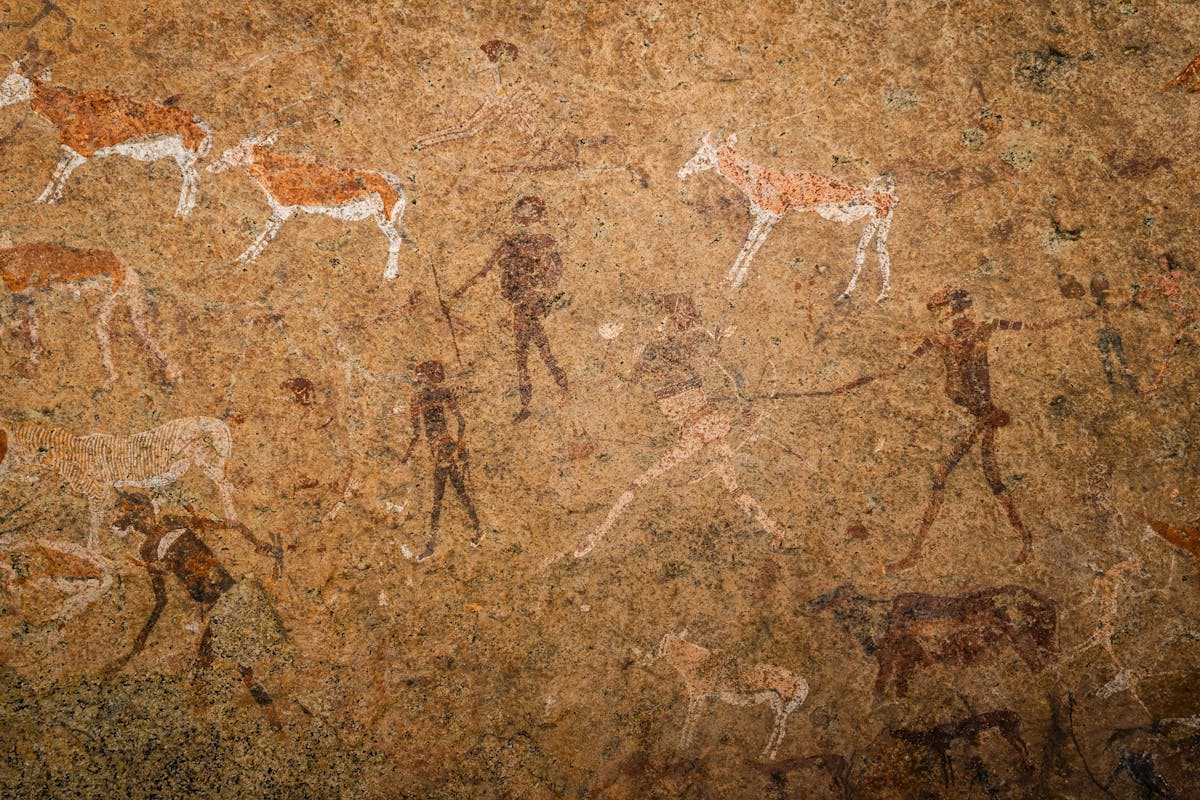

Amanda: Yeah, and let’s talk about one of your recent studies that you published with some students here at SPU, that is talking about that hunter-gatherer myth, really.

Cara: Yeah.

Amanda: That the men go out and do all the hunting and the women stay behind with the kids and gather from the seeds and the nuts and the fruit. Talk us through how what we’ve been generally taught is wrong, and then why it’s important to point those things out.

Cara: Yeah, there are so many pieces of this. I think the one thing that’s wrong is that culture, and cultures before our culture were static, that there is a moment in our history where everybody did the same thing and that is the true way to be a person or to be a community of people. That is just a false narrative, and thinking that we have some sort of perfect ancestral community way of life creates a whole suite of problems for us today as we manage current dilemmas in our relationship with other communities and cultures, as well as with ourselves.

The second thing is that because I approach all problems in human communities from a mobility perspective, I was very interested in this question of who’s moving and what are they moving to do, in this particular study sort of small-scale, typically foraging communities. One of the problems of the man-the-hunter/woman-the-gatherer tropes is that even though we’re talking about women and children gathering, the take-home message is that they’re not moving. They’re not mobile. They’re sitting in a little village not doing anything, and that’s never, ever been the case, ever. And so first of all, it’s just everybody is mobile. Everybody is moving because that’s how you manage small-scale societies.

The second thing is that everybody changes what they manage in a small-scale society based on season. And so even if you were to say there are some seasons where women and children might be gathering berries or whatever it is or digging for tubers or gaining access to some sort of plant material, fine. But there are other seasons in every community, and I should say men are doing that too. In some seasons, men are strictly gathering because everybody’s gathering because that’s the seasonal availability.

Amanda: Because it’s a harvest season, yeah.

Cara: Absolutely. And then there are other seasons where the fish are running, so everybody in the community is fishing, and that’s all you’re doing for three months. And then there are other seasons, usually very short, a-couple-of-weeks seasons where everybody in the community will hunt. And so this idea that everybody only is doing one thing for a long period of time: false. The idea that everybody is doing one thing for a whole year: false. The purpose of this study was simply to say there are very few cultures that have a taboo about who is bringing food into the community, because most cultures, most small-scale foraging communities, cannot manage with a rigid taboo against everybody doing something to help. It’s just not feasible. And so people who are interested learn how to go out and track and hunt. Children go. Women go. Men go.

There are two favorite examples that I have from doing this research. One is that it ends up that people who are in relationship really like to be together, and so men say, “I like to be with my wife. I want her to come hunting with me,” and so she does. And/or she says, “I want to be with my husband. We want to go hunting together, and so we do.” So lovely. And then I think getting to why I think this was so surprising for people is that there are also studies where the anthropologist will report, “Well, the men say that the men are going out hunting, but actually while we’re chatting about what great hunters the men are, the woman has spotted the game and killed it with her machete.”

Amanda: (laughs)

Cara: And so there is also this ongoing sense — people are people everywhere — that some people want to take pride in what they’re doing, and so they sort of undercut what other people in their community are doing. So you really have to read deeply and intentionally to find the subtext, to find all of these stories that once you add up are no longer anecdotes. Women are always there. I think that that’s what I want to say about that for now.

Amanda: Well, yeah, I think the reason, to me, that this sort of study, and really talking freely about the truth of how societies work …

Cara: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Amanda: The reason it’s important is it trickles into everything that we do within a household. This idea that the men are supposed to make the most money and the women are supposed to spend the most time with the kids and that there are exact right ways for things to be, because like you said, if you go back in time to, “This is the right way to do it, and we’ve been messing around with it. But if we can just get back to that basic idea, everyone will be successful,” when that’s not true at all. And of course what it leaves is at least one member of the family feeling as if they cannot be fully human.

Cara: That’s right. That’s exactly the danger of this kind of narrative.

Amanda: Right, that it feels so baked into our genes and our bones.

Cara: Yeah, and I think that’s true for both people in the relationship, right? The one person who feels called to do something and then is told, “Well, you’re not allowed to feel that call because your job is here.” And so women could feel that if they want to be in the workplace and feel like they have more things outside of the home. Men can feel that if they really feel called to be at home with their family or doing those day to day but they’re really being pushed or even ridiculed for not being “the provider.” And so I feel this is damaging relationships from both ends because in both situations … I mean, there are plenty of small-scale foraging communities where either you have egalitarian behavior and everything is shared 50/50 or where you have men who really enjoy carrying their babies around and they’re going to do all of the baby carrying. They’re going to do all of the trips to the river and weaving of the nets and all of that because that’s their choice.

“The one person who feels called to do something and then is told, ‘Well, you’re not allowed to feel that call because your job is here.’ And so women could feel that if they want to be in the workplace and feel like they have more things outside of the home. Men can feel that if they really feel called to be at home with their family or doing those day to day but they’re really being pushed or even ridiculed for not being ‘the provider.’ And so I feel this is damaging relationships from both ends ….”

Amanda: That innate sense of, “You can lean into what you’re good at,” and thinking of that idea that we can be led by our gifts and talents and calling, thinking of that as this very new enlightenment-era thing when that’s not really true at all. We all benefit as a society when people do what they’re best at.

Cara: Absolutely.

Amanda: Right? I mean, why shouldn’t we get to do what we’re best at?

Cara: Absolutely.

Amanda: In fact, you and I have talked about how you got into this very, very specific field in the first place, and I think it’s such a fun story. Do you mind telling that story? I’m sort of leaning into what you specifically have in you.

Cara: Yeah, no, absolutely. We have talked before about one of the reasons I became interested in locomotion is because I don’t see very well. My vision is very bad, and when I was in middle school and high school, I wasn’t able to afford contacts because I’m old enough that contacts were a luxury item, and so I had to have glasses and I was embarrassed. I was embarrassed for being the girl with glasses, and so I would wear them for math class so I could see numbers on the board, but I would never wear them. I wouldn’t wear them to PE. I wouldn’t wear them to school dances. I wouldn’t wear them at lunch time, and so I couldn’t see anybody’s face at all. And so the only way that I could recognize people in the gym or the classroom or whatever was by how they walked, by how they moved, which I think is also why I’m so interested in how people change their movement, because if I was in the lunchroom or if I was at a basketball game or if I was somewhere else, people do walk really differently depending on their task. And I probably would never have known that if I could have afforded contacts when I was 12. (laughs)

Amanda: (laughs) And then you would have missed out on this amazing research and study.

Cara: Yeah, no, it’s true.

Amanda: I find that to be true in a way that I wouldn’t have connected it with your work. But earlier in life when I was doing a lot of acting and spending a lot of time onstage, I always wanted the shoes that my character would be wearing very, very early in the process or at least something, like is it going to be heels? Because how they move and how they walk is so central to who they are. When I found myself moving as this character, I would say, “Okay, now I have her. Now I know who she’s supposed to be.” And how people move is so much of who they are. And I think that’s true across the board, like you said, but most of us, because we’re focusing on faces and other things, we’re not thinking about that as we go.

Give us some examples of why and how people intentionally change their gait, how they move. Because like you said, we don’t start one way when we’re babies and then walk that way the rest of our lives.

Cara: There are a couple of things that I think we know. Teenagers change their gait when they’re walking with their friends in, I guess it used to be the mall. I don’t know where young people walk anymore, but the studies are done with teenagers walking through the mall versus walking with their parents. So we know that gait changes, again, depending on your social context. We know that gait changes depending on whether you’re proud of yourself or whether or not you’re feeling tired or even ashamed. We know that footfall patterns change. Step to step variation changes. We know that in urban areas people walk faster than in rural areas, and so we have actually quite a massive amount of data. I’m not going to be able to pull it out of the top of my head, but there are cities that are known in the biomechanics literature for being the fastest cities, and those are places where people downtown walk at the highest average speed and then there are slow cities where people are more likely to amble. So we know all of those things.

I think that what we don’t know very well, and I’m interested in understanding this more, is as an anthropologist, we tend to think that someone’s body shape drives their options, and that’s because we look at the fossil record and we see shapes, and so we want to be able to make as many claims about those shapes as possible. So if you have long legs relative for your stature, we expect a certain kind of locomotion because we want to be able to say that now-extinct species with relatively long legs must have done these sorts of things. But I think I’ve mentioned to you before that my husband is adopted and he does not look anything like his adoptive parents, but he walks exactly like his dad. It is almost distracting to me how similar their gaits are, even though their morphology, their body shape, is entirely opposite.

And so this, I guess, goes back to your nurture versus nature. I think we have expectations that how you look drives your locomotor options, I would say, but I think there is this really strong nurture component where when you see parents with children, their children do tend to walk like them. We often just say, “Well, they’re related so blah blah blah.” But, I mean, they’re not, right? There’s a large proportion of our population who are not in family relationships with people they share alleles with, and so I feel like there is much more of a cultural component to locomotion that sort of guides what your options are for how you’re going to take a step.

Amanda: And even to take it to the psychology realm, like you were saying, you walk very differently, you carry yourself very differently when you’re feeling insecure or ashamed or exhausted.

Cara: Yep, absolutely.

Amanda: This study is like, most people have heard the TED Talk about the superhero poses, how basically you can go the other way, right? You can trick yourself.

Cara: Yeah. (laughs) Absolutely, you can trick yourself. I tell this to my students all the time about studying, but also about other things, that you absolutely, this is one of the fun things about being a human, is that you really can trick yourself into walking with confidence even when you don’t feel it. You have this top-down dynamic where you can turn that on and you can go into an interview with all of the confidence. It’s the same as you’re told to smile if you don’t feel happy, and then potentially your mood can shift. It is exactly the same with locomotion.

Amanda: That’s so fascinating to me. So what comes next for you? What’s your next big question that you’re going to tackle?

Cara: Well, actually right now I’m going back to my initial passion, which is women carrying loads, and this was how I got into the study of female efficiency and economy in the first place, and humans generally across the board are probably the best load carriers of the mammalian order. There is a quirk in how we understand how people carry loads differently on their bodies. I’ve studied people who carry loads on their shoulders, on their back, on their side, on their front, essentially different ways that people carry children. But there is a large swath of the human population everywhere in the world, across the globe, who actually carry loads on their heads, and we don’t know how it is that humans can carry loads on their heads for less energy than any other place on their body. This has been studied for about 30 years now in different ways: people on the treadmill, people in labs, people who have experience, people who don’t have experience, energetic studies, kinematic studies. But we think that we’re putting together a study that will … But we’ve never been able to figure it out, why some people in some parts of the world can carry 20‒40% of their body mass in water or household items on their head and not have any energetic change.

Amanda: Wow.

Cara: Wow.

Amanda: I’m going to start carrying things on my head.

Cara: You should.

Amanda: (laughs)

Cara: You can come into the lab, because we’re looking at this right now. We just don’t know how that is. We don’t know how it’s possible that you can add mass to your body and not experience any change in your energetic expenditure, because as we’ve said, it’s usually a pretty tight correlation. So we are investigating this right now and it’s looking to be really exciting.

Amanda: Okay. Nike, Adidas, Champion, start making, instead of backpacks we need headpacks.

Cara: Exactly. Headpacks. Yep.

Amanda: That’s so fascinating. Well, will you come back again when you have new and wonderful things to share with us?

Cara: Of course.

Amanda: Well, let’s end with our favorite last question that we ask everybody.

Cara: Okay.

Amanda: If you could have everybody in Seattle wake up tomorrow and do one thing differently that’s going to make the world a better place, what would it be? Besides carrying things on your head? (laughs)

Cara: Well, interesting. I really, really appreciated your analogy of walking in someone else’s shoes, and I think that having lived in Seattle for a really long time, I think we have a form of liberalism without empathy that is worrisome for me. We’re okay voting one way as long as it doesn’t actually cause our own taxes to rise or as long as it doesn’t actually interfere with our goals. I think that we need to understand that we do need to give something up to help other people be successful, and I think that taking on someone else’s gait, taking on someone else’s experience of the world is the best way that we can recognize what needs to change in our community for everybody to be able to fulfill their calling and understand their vocation.

Amanda: Yeah, the old adage of walking a mile in their shoes.

Cara: Absolutely.

Amanda: But it’s like walking a mile in their shoes carrying their load, right?

Cara: Yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Amanda: With their lack of water, all those things, so that we actually are willing to change ourselves to help them.

Cara: That’s right. Yeah, that’s right.

Amanda: Fantastic. Well, Cara, thank you so much.

Cara: Thanks for having me.

Amanda: We’re so glad to have you and so glad that you are teaching and producing students who are thinking differently and impacting the world.

Cara: They’re great. It’s easy.