Editor’s note: This feature was originally published in the Winter 2009 issue of Response magazine, vol. 32, No. 1.

Editor’s note: This feature was originally published in the Winter 2009 issue of Response magazine, vol. 32, No. 1.

In the Greek language, the word for “person” is prosopon, and that means literally “face” or “countenance.” I am only truly a person, that is to say, if I face other persons, if I look into their eyes and let them look into mine. To be a person is to be in relation with other persons. If that is true of personhood in general, then it is surely true more particularly of our identity as Christians.

In the early Church, there used to be a saying: unus Christianus, nullus Christianus — “one Christian, no Christian.” No one can be genuinely Christian in isolation. We are saved, not alone, but as members of the Body of Christ, in union with all the other members.

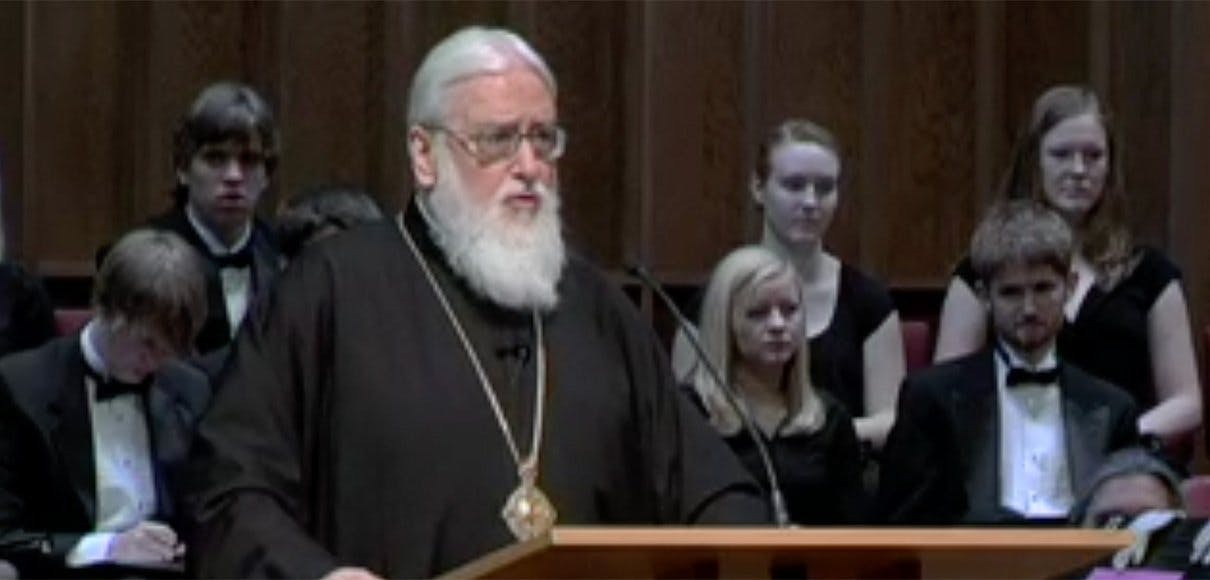

Hear Metropolitan Kallistos of Diokleia’s 2008 Alfred S. Palmer Lecture, “What Is Prayer.”

For me, therefore, as a Christian, it is vitally important that I should seek to meet other Christians, to understand them and to work with them, not only Christians of my own church family, the Orthodox Church, but also Christians in many other traditions as well. That is why I choose to give part of my time to travelling on lecture tours, and why I participate in conferences, seminars, and dialogues.

You may ask how it is that I, a Westerner, belong to the Orthodox Church. My journey into Orthodoxy began in England, where I was brought up in the Anglican Church. My parents were practicing Christians, so from my earliest years I was taught to pray and go to church. I can clearly recall my ambitions at 5 years old. I wanted to be one of two things: a bishop or a railway station master.

When I was 16, I was given a book token worth 7 shillings and sixpence. For some reason, I used it to buy a work titled The Desert Fathers by Helen Waddell. Reading the sayings and incidents in the lives of the desert fathers and mothers of fourth-century Egypt introduced me to a new world. It is curious — and I’m sure everyone has had the same experience — how certain things in our lives are instantly attractive. We sense at once, “This is for me.” I felt, “When I grow older, I want to learn more about this new world.”

It was also when I was 16 that I underwent what I consider to be my conversion. People often talk about being a “convert” as meaning the move from one Christian community to another. I don’t think that usage is strictly accurate. Conversion is to Christ. At 16, the Christian faith in which I’d been brought up suddenly came alive for me in an immediate way.

It was a year later, in 1952, when I had my first contact with the Orthodox Church. I was 17 and due soon to enroll at Oxford. By chance or by divine providence — because on the spiritual level there are no such things as coincidences — I went inside the Russian Orthodox church in London on a hot, brilliantly sunny Saturday afternoon.

As I entered the vast Victorian building, it was dark, and, coming in from the sunshine, I could see very little. My initial impression was that it was empty. There were no pews, because the Russian Orthodox stand for prayer — at least they once did in England, and they still do in many Orthodox countries. All I could see was a large expanse of polished floor.

Then, as my eyes grew accustomed to the gloom, I realized that the church was not entirely empty. There were a few, mostly elderly, people standing near the walls. There were icons on the walls, with lamps burning in front of them. There was, at the east end of the church, an icon screen with many lighted candles in front of it. Somewhere out of sight, a choir was singing. The service that the Russian Orthodox hold on Saturday evening, the vigil service, which lasts two to three hours, was in progress. And then, out from behind the icon screen, a deacon appeared. And I noticed that his vestment was torn, because the Russian community in London at that time was quite poor.

After this, my initial impression of the church being empty was succeeded by a quite different feeling. I felt overwhelmingly convinced that the church was, in fact, full — full of invisible worshippers. We, this small, visible congregation, were being taken up into an action much larger than ourselves. I felt a sense of the unity between our earthly worship and the worship in Heaven. I had a vivid sense of the living reality of the communion of saints.

I didn’t understand anything that was said, because it was all in Slavonic. But, again, as with the book by Helen Waddell, I felt an immediate attraction. Why is it that we often feel about something, “This is for me,” before we even know much about it?

I suppose people who fall in love do that. They get to know each other later on. I waited six years before joining the Orthodox Church. I wouldn’t say my mind was made up on that Saturday afternoon. But that experience gave a direction to my life, which meant I felt more and more that my “true home” was in the Orthodox Church.

When I began to read about Orthodoxy, I was impressed by a sense of living tradition. I felt, “Here is a church with deep roots in the past; a church that has not undergone the Scholasticism of the West and the Middle Ages, nor the fraction and breaking that took place with the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation, and that has not been profoundly influenced by the Enlightenment; a church that remains the church of the early martyrs of confessors, the church of the early fathers and of the ecumenical councils.” And this attracted me deeply.

Other things in Orthodoxy also appealed to me as I came to know it better. One was the mystical tradition of the Christian East. Another was the recognition that here is a church that in recent centuries has undergone tremendous persecution.

During the last 500 years, the majority of the Orthodox have been living under Islamic rule; they are tolerated up to a point, but subjected to constant pressure and treated as second-class citizens. During the Turkish period, there were, in the Greek, Serbian, and Bulgarian churches, and among the Arab Orthodox, a constant series of “new martyrs” who died for their faith. And with the rise of communism, the Orthodox underwent a much more vigorous persecution by militant atheists. This continuing experience of persecution and martyrdom has meant that Orthodox Christians in recent centuries have been very close in spirit to the first Christians. I was received into the Greek Orthodox Church in England in 1958. At the time, there were very few English Orthodox around — today there are many more of us. I remember when the Greek bishop received me, he said, “Please understand that here in Britain you will never be able to be ordained as a priest. We only ordain Greeks.”

Well, I was ordained deacon after I’d been a layman for about seven years. And then I was ordained a priest. And then a monk. And all of this was not by my initiative; it was the new Greek bishop who came to England in 1964 who pressed me to accept service in the church, and who sent me to be a monk on the island of Patmos. I’m still a brother of the Monastery of Saint John there.

I remember the advice of Father Amphilochios of Patmos to me when, after a year in the monastery, I was appointed to teach theology at Oxford University. Now, he’d never traveled to the West; he had no firsthand knowledge of the position of Orthodoxy there. But he understood, I think, very well, how things would be for me. He said, “You will be the only Orthodox teacher in the theology school. You may sometimes feel isolated, and you may sometimes feel threatened. But do not be afraid.”

He was very emphatic about that. “Do not allow fear to make you unduly defensive and apologetic about your faith. Do not allow fear to make you, on the other hand, unduly aggressive about your faith. Do not make it lead you to attack other Christians. Neither be defensive nor aggressive; simply be yourself.” v It was good advice. And I’ve tried to live up to it ever since.

I often speak of Orthodoxy as a “fullness” of faith and spiritual life. And it was that which attracted me to it. But I would at once add, in the words of Saint Paul, “We have this treasure in vessels of earthenware.” We Orthodox have many reasons to be conscious of the fact that we are not worthy heirs of our rich inheritance, that we do not use the treasures that God has given to us in the way that we should. It is through our contacts with other Christians that we can learn to understand our own faith better, and to live our Orthodoxy more truly.

Metropolitan Kallistos (Ware) of Diokleia is one of the world’s foremost Orthodox Christian authors, teachers, and scholars. Best known for his books The Orthodox Church and The Orthodox Way, Metropolitan Kallistos became a bishop in the Greek Orthodox Church in 1982 and was elevated to metropolitan (archbishop) in 2007. He frequently lectures on Eastern Christianity to Western audiences.