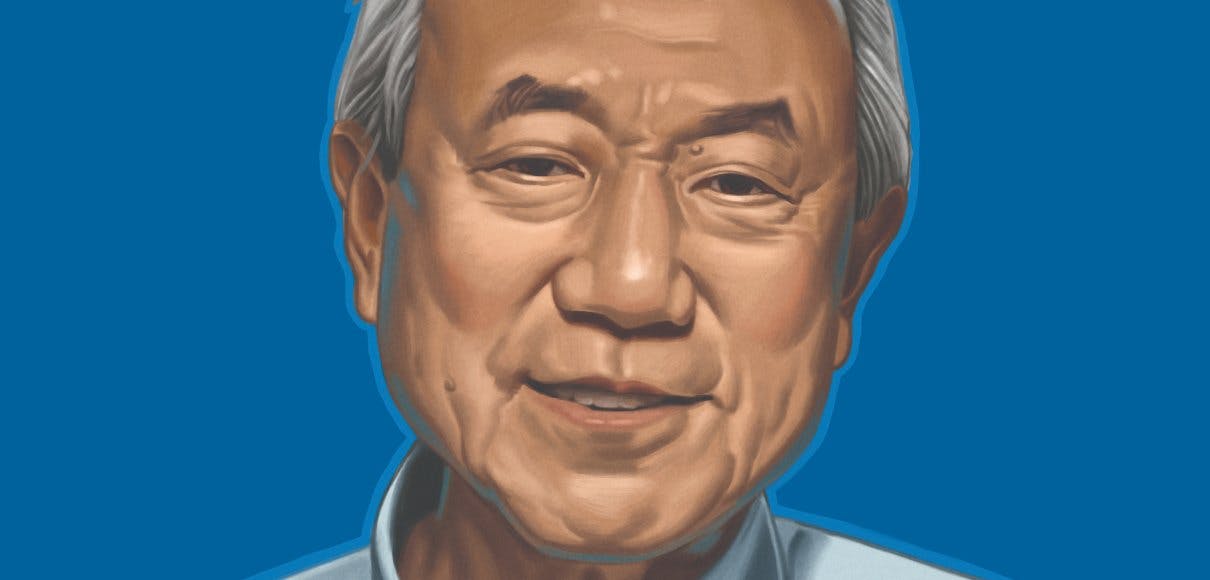

WHEN CHI-DOOH “SKIP” LI ’66, stepped off the plane in Guatemala in 1982, he was no stranger to the country. Li lived there for three years as a young boy before moving to the United States and eventually becoming a lawyer in Seattle, Washington.

Li flew to the Western Highlands of Guatemala’s Ixil Triangle to determine the feasibility of a new idea: Could rural families work their way out of poverty and begin to accumulate generational wealth if they were given the opportunity to own land?

Two years later, Li founded his faith-based nonprofit, Agros International, to help break the cycle of poverty in Latin America. With the help of donors, Agros purchases large tracts of land to create a village. Families then build their own agricultural businesses, work toward land ownership, and jointly manage the community.

When Agros began in 1984, Guatemala was in the middle of a civil war between government forces and Marxist rebel groups. “The indigenous people I met had fled the violence,” Li remembered.

María de la Cruz de Pérez experienced it firsthand. “In 1982, I said goodbye to my family and left with the people who went to the mountains,” she said.

“They killed women, men, little girls, pregnant women, old men, and old women. Whatever kind of person they came across, they killed,” she said. “They arrived at 6 in the morning. They burned people in their houses, and my mom was shot and killed.”

De Pérez and her husband eventually settled in a distant village. Their daughter Feliciana Raymundo remembered, “My dad didn’t have a job. He didn’t have enough land to plant crops to harvest.”

Although the civil war was devastating for Guatemalans, the challenges they faced went much deeper.

“This poverty [went] back hundreds of years to the time when the Spanish Conquistadors came in and took land — vast, vast swaths of land — away from the indigenous peoples. That kind of poverty creates a sense of despair that is unspoken, but always present. We had to defeat that despair in people,” Li explained.

In Guatemala, the gap between the wealthy and the poor is particularly stark. According to the U.S. Agency for International Development, nearly two-thirds of Guatemala’s agricultural land belongs to just 2.5% of farms.

Land ownership feels impossible for the indigenous and rural poor. They don’t earn enough to purchase farmland, and banks are unwilling to lend them money.

That’s where Agros comes in. Agros helped establish 45 villages in Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Mexico, equipping 7,300 farmers to own land for the first time.

“With the help of Agros, my mom and dad bought land,” Raymundo said.

In 2020, Agros villagers received 758 land titles. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Agros provided personal protective equipment to 2,060 people and emergency food supplies to 2,419 people.

“Poverty is complex,” said Agros President Alberto Solano. “It’s multi-dimensional. Therefore, we need to provide a solution that can see a family holistically.”

Agros educates villagers about farming, business practices, health, and hygiene, and it supports families with maternity care, well-child checks, and small loans for women’s enterprises.

“We help them build their homes,” Solano says. “We build schools, and they establish their own agricultural businesses. Over seven or eight years, with the profit from their businesses, they can pay back the land and become owners.”

Agros helps farmers produce the best quality crops that will command top prices in the market. It isn’t subsistence farming. The goal is to help them sell not only to local markets, but eventually to regional, national, and international markets, where growers can earn significantly more for their crops.

“Our model takes time, but it’s holistic and comprehensive, which means we can provide a long-lasting solution,” Solano said.

The idea for Agros began when Li was a young Seattle lawyer. Sitting in church one Saturday night, he heard a guest preacher, Juan Carlos Ortiz, speak about the brutal civil wars in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua.

Ortiz shared how he’d read in the newspaper that the United States government was sending hundreds of millions of dollars to the Central American countries to buy weapons, Li recalled. “He said, ‘What a shame because with that kind of money, you could buy up all the land in Central America for the poor and get rid of the Marxists.’”

Back home that night, Li immediately started brainstorming ideas.

“Over seven or eight years, with the profit from their businesses, they can pay back the land and become owners.” — Agros President Alberto Solano

A founding partner of the Seattle law firm Ellis, Li & McKinstry, Li loves his legal career. He felt called to be a lawyer, just as he felt called to help people in Central America. No matter what our career or vocation might be, “We are called on to serve,” Li said.

The political science graduate was SPU’s 1992 Alumnus of the Year and has served on the Board of Trustees. Li was SPU’s commencement speaker in 2000 and 2019, and he has also been a popular guest lecturer for various classes at the University.

Li built Agros on an economic model that seeks to do good for God’s kingdom: Using business principles not as tools for maximizing personal profit, but to create change in the lives of people and their communities.

He sees relationships as key to his work, and Li — who is fluent in Spanish and in Mandarin — regularly visits Agros villages in Central America, where he talks, prays, and worships with local farmers in Spanish.

Agros by the numbers

231

Number of acres cultivated by Agros farmers

650

Number of families served

758

Number of land titles granted to villagers

At age 13, his son Peter joined him on a trip to Guatemala. Visiting the home of a village leader, the family prepared bowls of warm chicken soup with potatoes and vegetables for Li and his son. “I’ve had so many meals in people’s homes,” Li said. “They are absolutely generous.”

Many Agros villagers were praying for his family when Skip lost his first wife, Cyd Vice Li ’67, to cancer in 2016. When he returned to Guatemala in 2022 with his second wife, Elizabeth Converse, the Agros staff surprised him with a 40-year anniversary celebration of his initial trip. The reunions were filled with tears and hugs from villagers he had met in earlier years when he was starting the nonprofit.

“Agros is going after Jesus’ call to love the poor,” said Molly Delamarter ’01, former board chair at Agros. “In this case, love isn’t just ‘send your money.’ Love is coming alongside to support the individual and the family in really envisioning a better future for them.”

The nonprofit’s mission is about creating lasting relationships with brothers and sisters in Christ and equipping families to dismantle generational poverty.

“There’s no dignity in just being the recipient of gifts,” Li said. “The dignity is from their hard work to pay off the land. You look on their faces, you see the sense of dignity: ‘I am someone now because I own my own land.’”

Illustration by Scott Anderson