An idea for a toilet led to a $5,000 prize and a plausible plan to aid a community on the other side of the world.

The plan started on a toilet. Or at least with two students focused on a toilet.

SPU juniors Lhakpa Tenzing Sherpa and Amy Frederick visited the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in late January, researching ideas for the University’s 14th annual Social Venture Plan Competition.

The two global development studies majors discovered the foundation’s “Reinvent the Toilet” challenge, which featured innovative technologies aimed at improving sanitation for the world’s poor. They wandered through the exhibit of toilet designs, including one that incinerated waste products.

“I remember joking with Amy, saying ‘What if we take this to Everest base camp?’” Lhakpa Sherpa said. “Then we talked about it more and saw it had potential.”

They shared the idea with their teammates, Jenna Haines and Ryan Kennedy, also global development majors. The team wanted to serve the ethnic Sherpa community in Nepal, in part because Lhakpa Sherpa was born and raised there and had shared about the community’s economic challenges.

The alternative toilets at the Gates Foundation sparked a viable connection. “There’s a problem with unmanaged human feces at Everest base camp,” Lhakpa Sherpa explained.

“Entrepreneurship sometimes isn’t just about having a great idea. How well you execute your idea is everything.”

– Mark Oppenlander

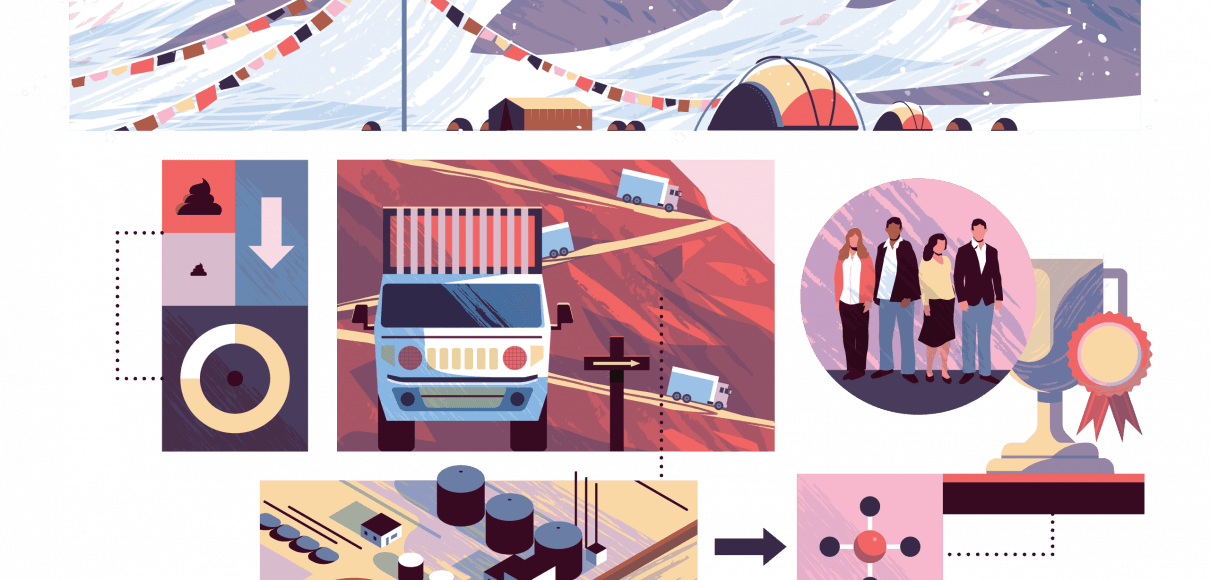

Up to 35,000 climbers visit Everest’s base camp each year, leaving behind roughly 25,000 pounds of fecal matter that has overwhelmed mountaineering companies and local communities. The waste contaminates drinking water, spreads diseases, and sullies the landscape for neighboring Sherpa communities.

The students got to work on their business plan for the fast-approaching social venture competition held last April. The competition is required for global development majors.

Hosted by the School of Business, Government, and Economics’ Center for Applied Learning, the Social Venture Plan Competition encourages students from different disciplines to tackle a social need through a sustainable business model. At this year’s competition, students proposed reducing air pollution in

India by providing gas-to-electric conversion kits for mopeds. Another plan looked at transporting greenhouses to provide fresh fruit and vegetables to rural areas of Alaska.

Lhakpa Sherpa and his team named their venture Safa Himal, which means “clean mountain” in Nepali. The plan would provide portable toilets at base camp that could dehydrate human waste, reducing its size and weight by up to 75%. The dehydrated feces would then be transported down the mountain to a newly

Lhakpa Sherpa and his team named their venture Safa Himal, which means “clean mountain” in Nepali. The plan would provide portable toilets at base camp that could dehydrate human waste, reducing its size and weight by up to 75%. The dehydrated feces would then be transported down the mountain to a newly

constructed biogas processing plant and converted into methane fuel. The business creates new, viable jobs for a community used to low wages and scarce job options outside of working as expedition guides.

And the concept fit with the students’ philosophy of global development. “It’s not about what we think people need; it’s about partnering and working together to accomplish what they know they need,” Haines said.

Kennedy handled the project’s social impact. Haines managed the logistics. Frederick oversaw marketing, while Lhakpa Sherpa worked on the cost projections, thanks to his Nepali contacts. The team wrestled a mountain of work into a presentable business plan in a few weeks.

“Entrepreneurship sometimes isn’t just about having a great idea,” said Mark Oppenlander, director of the Center for Applied Learning. “How well you execute your idea is everything. Watching them take Lhakpa’s idea and run with it and then use the strengths of the various team members to their advantage was just genius.”

Instead of pitching their venture at a live competition, the pandemic turned the event into an online virtual showcase. University closures meant the students were dispersed to work from home and other locations. Yet despite its challenges, that separation turned into an advantage for the team during the competition.

“It allowed us to focus on our time with the judges,” recalled Haines. “And we could help each other answer questions.”

In the end, the group’s vision, synergy, and persistence paid off. On April 22, the venture that started as a lighthearted joke about human waste won the competition’s $5,000 grand prize, which the team hopes to use toward manufacturing the toilets.

For Lhakpa Sherpa, the plan that he and his friends devised is the real prize. “My father, Chhewang Nima Sherpa, summited Everest 19 times. But I lost my dad in the mountains at a very young age,” he said. “I never thought I’d be as attached [to] the mountains as I am right now. This takes us one step closer to giving back.”